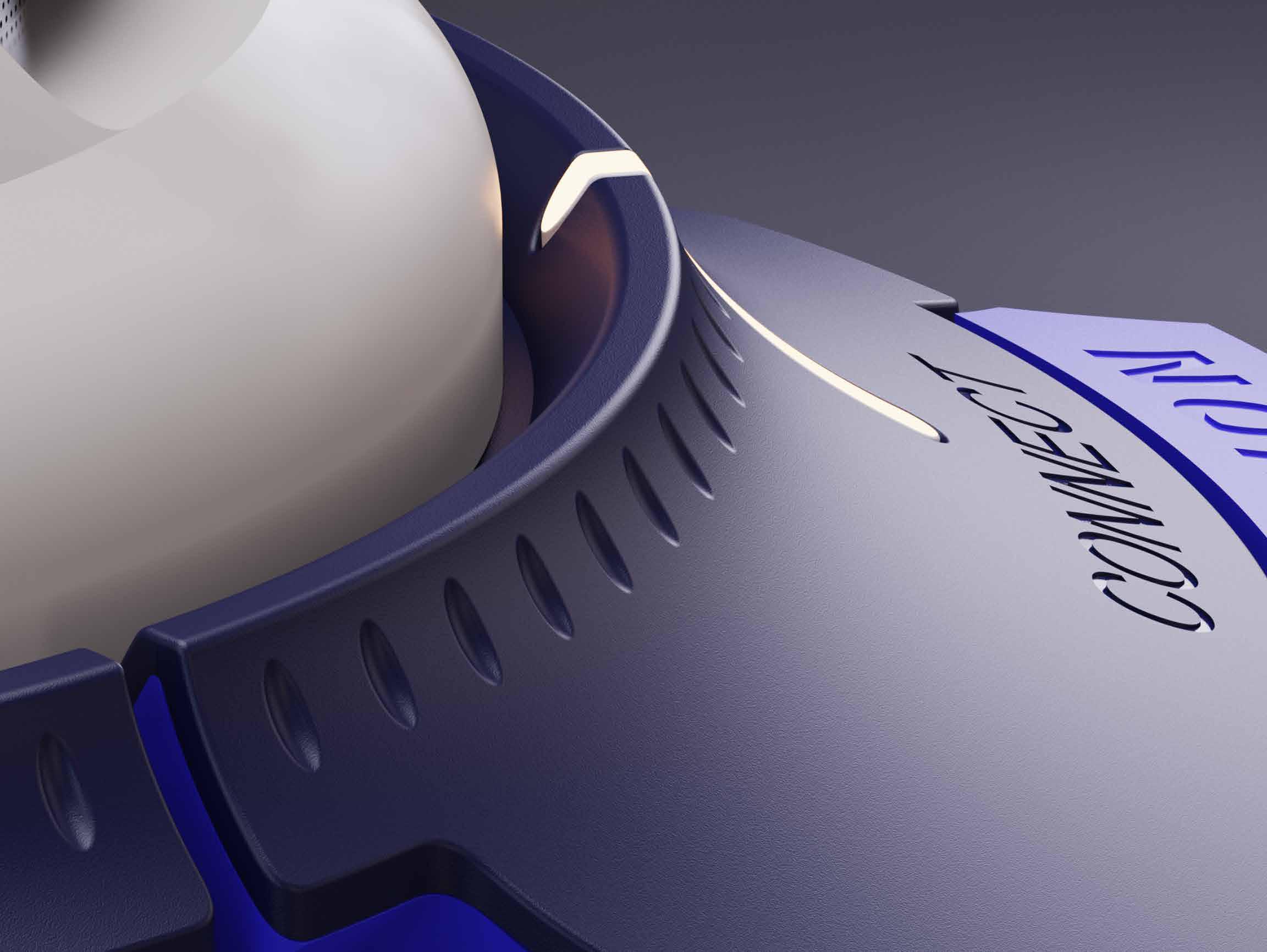

Picture: Kongsberg Digital

For decades, the practise of Noon Reports is elementary in shipping as they form an integral part of ship-to-shore communication.

Still today, the Noon Report remains a widely spread and commonly used form for monitoring vessel operations and performance by shipowners and charterers. Countless shipping companies still rely on Noon Reports to understand and monitor what is happening on their ships.

In general, throughout maritime voyages, the Noon Report is sent by the ship’s Master to the shoreside organisation and offices at a fixed time on daily basis. Normally it is sent during or short after noon, hence its name.

Historically, the only moment a ship could determine accurately its position in the open ocean was at noon every day. At all other times the position of the ship was based on an estimated calculation from the previously determined position. To determine the accurate position of the ship, starting in the 18th century, the sextant and the chronometer were used to calculate the longitude in the morning and the latitude at noon (for the vessel), i.e. when the sun was passing through South.

Exactly knowing the position of the ship was crucial to determine what course to steer. Gradually, with improved communication and an obvious advantage in knowing the best estimated time of arrival, reporting a vessel’s latest position became a common practice, and hence the story of the noon report began. Initially noon position reports were being sent using telex and radio.

Over the years, the Noon Report has grown to provide a snapshot of what has happened on board the ship since the previous noon, i.e. during the last 24 hours. In other words, Noon Reports meanwhile give a regular snapshot of vessel performance and condition.

Today’s Noon Reports exist in all forms, but basically they are a data sheet being prepared by the Chief Engineer of the vessel, on a daily basis.

Besides the vessel’s position (AIS data), the Noon Report contains now a variety of other important and relevant data points on the voyage that can subsequently be used to assess performance:

- average speed since the previous Noon Report

- distance sailed

- ocean and swell conditions

- weather conditions

- average RPM of the engine(s)

- propeller revolution and slip

- quantities of fuels, lubricating oils and water remaining on board (RoB)

- ETA in the next port of call, and much more

This regular input of a huge number of variable data onboard through the Noon Reports is meant to serve various purposes:

- monitor vessel and energy efficiency

- assess the performance of the ship based on its speed and environmental forces, including weather conditions

- calculate and keep track of the consumption of lube oils and water (also helping to plan bunkering operations)

- calculate voyage profitability

Moreover, ship managers use Noon Reports also for monitoring and assessing the difference in performance against the terms agreed in the charter party, or between two similar types of ships (or sister ships) and to detect underperformance or possible room for technical improvements.

For decades now, Noon Reports have thus served as the single source of truth for data collection related to vessel performance monitoring. But although being a modest first step towards working with vessel data, it is obvious and clear that the Noon Report in its historic form is representing a few substantial shortcomings.

The enormous variance in reporting standards and questionable reliability are often cited as some of the main critical objections.

Because these reports are produced manually, often according to the specific requirements or guidelines of an individual shipping company, charter party or ship manager, the diversity of their input and the way information & data are collated can vary widely. This is resulting in Noon Reports being provided in various formats to not just ship owners and managers, but also to (sub-)charterers, weather intelligence providers, ports and terminal operators, oil companies, commodity traders, ship agents, and more.

The optimisation goals of the maritime industry – instigated by inherent fierce competition on the one hand and by the mounting pressure coming from regulatory decarbonisation objectives (IMO, EU) on the other hand – can only be achieved by a reliable and trustworthy output from analytics platforms. This is requiring shipboard data input to be of high quality, standardised and interoperable.

Recently, initiatives in the industry to pursue such highly recommendable standardization of the reporting format are beginning to see the light of day, but as with any technical standard, critical mass in the industrywide adoption will be key to the respective utility.

With vessel operations and the maritime supply chain across the globe becoming increasingly complex, all efforts to optimize vessel and fleet performance should undeniably be supported by the capacity to analyse each individual component of the entire process in granular detail.

What started and evolved as a sheer position report has meanwhile slowly but steadily become so elaborate – because of this complexity – that it takes the crew several hours of morning time to collate (often manually) all the data required from various (remote) areas of the ship, e.g. the engine room, the cargo control room, the bridge. In other words, the administrative workload is high and thus time-consuming.

Being observed, collected, tabulated and reported manually by the crew, this dataset is particularly prone to (human) errors due to its operational ambiguity and dependency on crew members’ credibility.

But besides data quality and missing standardization, the most critical element in this argument is data frequency.

With a sampling frequency of approximately 24 hours, Noon Report data can only provide a low-resolution dataset. Providing datapoints only once every 24 hours is not sufficient nor adequate to produce a proper and meaningful vessel performance analysis.

Weather data (wind direction, wind force, sea and swell condition) and speed as included in manual Noon Reports are general values, often taken at the time of report preparation or calculated as average over the last 24 hours.

“Noon-reported weather to be erroneous 68% of the time when compared to data from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration”

Needless to say, meteorological conditions can change significantly per hour, especially at sea. An average value of wind speed observed at noon might vary significantly from windspeed during the previous night. Even so, average speed is quite a meaningless figure, unless the speed is constant for 24 hours, which in reality is a theoretical assumption.

Knowing that a vessel’s fuel consumption generally increases with the square of the speed, Noon Report-based speed data are simply not granular enough to produce accurate and reliable speed & consumption curves for predicting purposes (decision-making algorithms). Analyses conducted by the University College London and Hyundai Heavy Industries revealed Noon Report-based S&C curves to be 15 to 20% less accurate in terms of predicting fuel consumption when compared to continuous data-based reporting.

Considering these weaknesses, shipping is facing a challenge: while the maritime industry is required and urged to increasingly become more data-centric, the commonly used method to gather critical onboard data is still based on these Noon Reports prepared and submitted by crews, to a large extent in its manual way.

Automated data collection and IoT solutions built for the maritime industry are coming to the rescue here. Digitalising this entire process will see the industry moving gradually away from manual Noon Reports into the direction of more holistic Vessel Reports.

Digital Vessel Reports provide a more reliable set of data to form the basis for high-quality vessel performance metrics calculations, comprehending real-time values, weather conditions, engine and equipment conditions, independent of any exposure to human error.

Not only removing the administrative burden and time-consuming redundant work for masters, chief engineers and designated crew members, digital reports are being prepared with the help of AIS, collecting real-time data from the sensors, and integrating the same with weather reports to generate high-quality vessel performance indicators.

The maritime industry is navigating into a new era, but only slowly. Although the use of real-time sensors and flow meter data is increasingly becoming an established practise, and while there is currently a strong drive to equip newer vessels and new builds with advanced high-frequency sensors that will collect and share data in real-time, the reality is that a substantial part of the world fleet still may not yet be fully equipped with adequate sensors.

Fleet Operations Centre (picture: Jungmann Systemtechnik GmbH)

Merchant ships are complex digital entities, capable of generating vast amounts of data which remain today to a large extent un(der)utilised. The successful utilization of IoT and sensors in the maritime industry requires a forward-thinking approach to maximize the proven benefits of Industry 4.0 in shipping.

By embracing IoT onboard of ever becoming larger cargo vessels, shipowners and charterers will not only benefit from removing human intervention, administrative burden and the inherent risk of human error during the data collection process. It will offer shipping companies the potential to unlock operational and commercial value by dramatically increasing the number of data points which can be collected, and by aggregating these in a structured process to generate frequent high-quality and trustworthy datasets.

By implementing onboard IoT, which is supporting data-driven decision making, vessel operators and ship managers will gain full visibility of vessel performance and unprecedented insight into the operations of their entire fleet.

With Sealution’s product offering we want to chart this course towards smart shipping by providing seamless IoT connectivity below deck, enabling the maritime industry to unlock and transport crucial data on board of merchant vessels.